According to recent reports, Russia has begun redeploying advanced air-defense systems and other military equipment from its bases in Syria to eastern Libya. This development comes on the heels of the Assad regime’s collapse which created a seismic shift in regional dynamics. In 2015, when Russia intervened militarily in Syria’s civil war, the Assad government was teetering on the brink of collapse, controlling less than 20 percent of Syrian territory. For Moscow, the Syrian conflict was an opportunity to draw a red line against perceived Western support for regime changes following the Arab Spring. Russia’s military involvement, which was relatively low cost from 2015-2020, allowed it to not only stabilize Assad’s government but also showcase its military capabilities and enhance its international prestige. The conflict was also a way for Russia to test its advanced weapons systems and train its military forces in a highly specific, but still very real combat environment. Moscow’s intervention established Russia as a key player in the Middle East and painted it as a reliable ally, which helped it create future partnerships in Africa. For Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Russian military’s power projection in Syria became a key part of his opposition to the West and strategic competition with Moscow’s adversaries.

For years, Russia’s naval facility at Tartus, and the Khmeimim airbase in Latakia allowed it to maintain a relatively light yet strategically significant footprint in Syria. The Khmeimim airbase, in particular, was essential for supporting Russia’s operations in Africa. However, with the takeover of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the future of Russia’s presence in Syria is opaque, with its highest priority likely being to secure its main bases at Tartus and Khmeimim while maintaining a degree of political influence in the region.

Moscow’s ability to quickly adapt its approach in the face of Assad’s downfall—especially in its dealings with HTS—offers it some hope of striking an agreement with the group to retain access to these bases, even if the U.S. and some of its NATO allies will be working to convince HTS to jettison Russia’s military presence altogether. Russia does maintain some leverage in its negotiations with Syria’s new power players, despite its brutal operations during the civil war and unpopular decision among the Syrian public and HTS to grant Bashar al-Assad political asylum. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, Russia possesses a unique advantage in providing a pathway toward international legitimization for HTS. Regional dynamics also play in Moscow’s favor. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt may prefer to see Russia retain its presence in Syria as a counterbalance to Türkiye’s expanding influence in the region. These states, wary of Türkiye’s growing role in Syria and beyond, might tacitly support Russia’s continued presence to preserve a balance of power in the region. Furthermore, Russia’s 2015 intervention and continued involvement in the Syrian conflict allowed it to build relationships with various other armed opposition groups and non-state actors in Syria which could provide alternative avenues for retaining influence in the country and potentially be leveraged in negotiations.

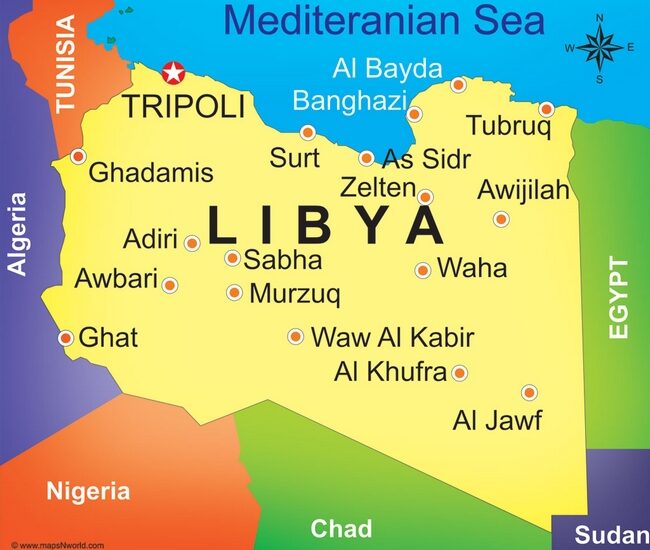

Nevertheless, Moscow recognizes that it cannot rely solely on the outcome of its ongoing negotiations with HTS to maintain its foothold in the Middle East and Africa, which has prompted its redeployment of equipment from Syria to its bases in eastern Libya. U.S. officials have also indicated that Moscow is exploring long-term docking rights in the ports of Tobruk and Benghazi, strategically located just 400 miles from Greece and Italy. Such a Russian presence in the Mediterranean would enhance its ability to project power into North Africa and counter NATO’s presence in the region. At the same time, Libya’s relative proximity to Russia, as compared to the rest of the African continent, positions it as a gateway for its expanding operations in Africa, mainly conducted by Africa Corps (formerly Wagner Group).

Eastern Libya, controlled by General Khalifa Haftar, has long been a center of Russian activity. Haftar has relied on Russian military support in his fight against Turkish-backed forces in western Libya. The Wagner group, and now Africa Corps, has played a key role in supporting Haftar’s forces, using his facilities as staging areas for broader Russian operations, including in Mali, Burkina Faso, and the Central African Republic. Recent reports have indicated that Russian cargo aircraft have already stopped over in Libya on their way to Mali multiple times this week.

These developments raise not only strategic concerns for Western powers but also significant human rights concerns. Russia’s expansion of military activity in Libya, in which Wagner has been present since 2018––despite its publicized withdrawal in 2020 when the group placed boobytraps and landmines killing hundreds of people––raises concerns about the furtherance of human rights violations throughout Africa. Russia’s and Africa Corps’ growing presence and influence in Libya also may exacerbate the concern of human rights abuses against migrants held in Libyan detention centers and throughout other regions where Africa Corps operates, like the Sahel.

Human Rights Watch, a non-profit organization that tracks human rights abuses globally, released a report in early December accounting for civilian abuses by Africa Corps, along with Malian forces. Since May, the report claims that Africa Corps and Malian forces “deliberately killed at least 32 civilians, including seven in a drone strike, forcibly disappeared four others, and burned at least 100 homes in military operations in towns and villages in central and northern Mali.” Human Rights Watch has documented a host of abuses in Mali by then-Wagner Group since its arrival in December 2021. Since the UN peacekeeping mission, the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), withdrew from the country at the end of last year, there is concern that the number of civilian abuses by the mercenary group may be higher than reported. Human rights abuses by Africa Corps have also been observed in other countries where the group is present such as the Central African Republic, where abuses such as the raping of teenage girls near the group’s bases have been reported.

However, reports of human rights abuses have not deterred Russia’s expanding operations in the region. Initial declarations by Russia cite Libya as the center and starting point of Africa Corps’ expansion, according to the Polish Institute of International Affairs. However, it was initially unable to execute such expansionist goals. At the beginning of 2024, Russian troops numbered approximately 800, with little activity occurring in the country. By May, watchdog group All Eyes on Wagner estimated these numbers to have increased to 1,800. According to the Institute for the Study of War, Russia sent an estimated 6,000 tons of weapons and equipment to Libya via-Syria in March and April 2024 and refurbished a number of airbases there. On December 13, ItaMilRadar, a website that tracks military flights over Italy and over the Mediterranean Sea reported that two Russian aircraft—specifically two Ilyushin-76TD—made stops at Al Khadim airbase near Benghazi, potentially creating an airbridge between Russia and Libya.

With the changing geopolitical dynamics in Syria, it is likely that Russian logistic infrastructure in Libya will rapidly expand. However, Syria served as a critical logistical hub for Russia’s operations, providing an essential stopover point en route to Libya. If Russia is not able to retain its Syrian bases in some capacity, its future expansion efforts in the region will become significantly more challenging. Libya, despite its strategic importance, cannot fully replace Syria in terms of logistical capacity, as the weight and scale of equipment Russia can transport to Libya is far more restricted due to the much larger distance between Russia and Libya.

Source: The Soufan Center